Catholic schools’ spokesman Michael Drumm says ‘amalgamation is way forward’ by Joe Humphreys.

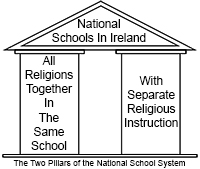

Creating more diversity and inclusiveness was the flagship enterprise of former minister for education Ruairí Quinn. He set up the Forum on Patronage and Pluralism in the Primary Sector on his first full day of office, and at one stage promised to wrest half of the State’s 3,100 primary schools from Catholic Church control.

To date, however, the church – which is patron to more than 90 per cent of primary schools – has yet to hand over a single school to another patron, although it did merge two schools in Basin Lane, Dublin, last April to allow Educate Together to move into a vacant building. One Church of Ireland school in Co Mayo transferred to Educate Together last September.

Mr Quinn’s successor, Jan O’Sullivan, insists that there is still life in the process but few people in education share her optimism. As the impasse continues, she is facing calls within her own party for a re-examination of the policy, amid claims that it allows the church to dictate both the pace and the nature of reform.

Members of the Oireachtas Committee on Education, including chairwoman and Labour TD Joanna Tuffy, have expressed concern that the divestment process is leading to “segregation on religious grounds”.

In a report on planned legislation governing admissions, the committee echoed some of the concerns of another Labour member John Suttle, who produced a widely discussed report in 2011 on the “Catholic-first” school entry policy. Suttle, who stepped down from the board of management of his local school over perceived Catholic discrimination, says “divestment is a Catholic process. It’s a way for the church to get the department to set up a non-Catholic school in an area so it can implement a ‘Catholic-first’ policy in its own schools.”

He says this is “creating segregation where there wasn’t any” and runs counter to the recommendations of the forum on patronage and pluralism, which reported in April 2012. “The forum never recommended a system where kids would be segregated on religious grounds,” says Suttle.

O’Sullivan however argues that the process is helping to give parents “a greater choice of school ethos”. She says: “Personally I would like to see the divestment moving much quicker. However, it is a complex process that involves the agreement of a range of stakeholders and that takes time. In 2015 I will be looking at the current arrangements for divestment to see if changes can advance the process.”

Fr Michael Drumm, chairman of the Catholic Schools Partnership, believes part of the problem was raised expectations, and he says Quinn’s talk of a 50 per cent change to patronage “scared local communities”. The transfer of schools to other patrons has proved difficult for a variety of reasons, including “huge local hostility”.

Arguing that the original plan is no longer realistic, he says “amalgamation is the way forward”. However, to achieve this, “financial supports need to be kept”. When schools merge, they find they can only access one set of grants rather than two, and if the department agreed to protect their collective funding , “it would help”, says Fr Drumm.

Educate Together also says the process needs to be better financed, pointing out that each school opening is costing it about €100,000, money it has to raise almost entirely through fundraising.

Debate is set to intensify when the Admission to Schools Bill comes before the Oireachtas as it reaffirms the right of denominational schools to give preference to children of a particular faith. The department has justified the retention of this right, articulated in section 7 of the Equal Status Act 2000, on the grounds that parents now have a greater choice of school patronage.

However, the office of the ombudsman for children has called for section 7 to be amended so no publicly funded school can discriminate on religious grounds. The forum also advocated a review of section 7 on the grounds that it could impede the department’s “duty to provide for the education for all children”.

Quinn rejected this advice, along with the forum’s recommendation for rule 68 of the primary school code to be “deleted as soon as possible”. The rule states: “Of all parts of a school curriculum, religious instruction is by far the most important” and therefore “a religious spirit should inform and vivify the whole work of the school”.

Prof John Coolahan, the forum’s chairman, says Ireland cannot ignore the international context and its obligations under human rights conventions. “What I was hoping to do in the context of the forum was to avoid conflict at local level,” he adds. If people could see change happening on the ground, “you wouldn’t have social conflict”.

However, given the slow pace of progress in divestment, amid changing demographics and a rise in secularism, “I do believe it could become much rougher.

“This [the divestment process] was a way forward and I think the church were unwise not to adopt it as a rational way forward, which had been evolved in dialogue in a democratic society, whereby there was nobody closing down denominational schools.

“By holding on so tight to 92 per cent of the schools, denominationally controlled, I think they are being short-sighted, even in their own interest.”